The 2020 local elections are a true challenge for the Ukrainian political domain. In addition to having the electoral system changed, and the restrictions introduced because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the elections will be remembered for the high amounts the parties and candidates spent for their campaigning on the Internet. Moreover, the advertising campaigns of some parties and politicians on the social media could also be seen on the “silent days” – the period of time when any campaigning shall be prohibited.

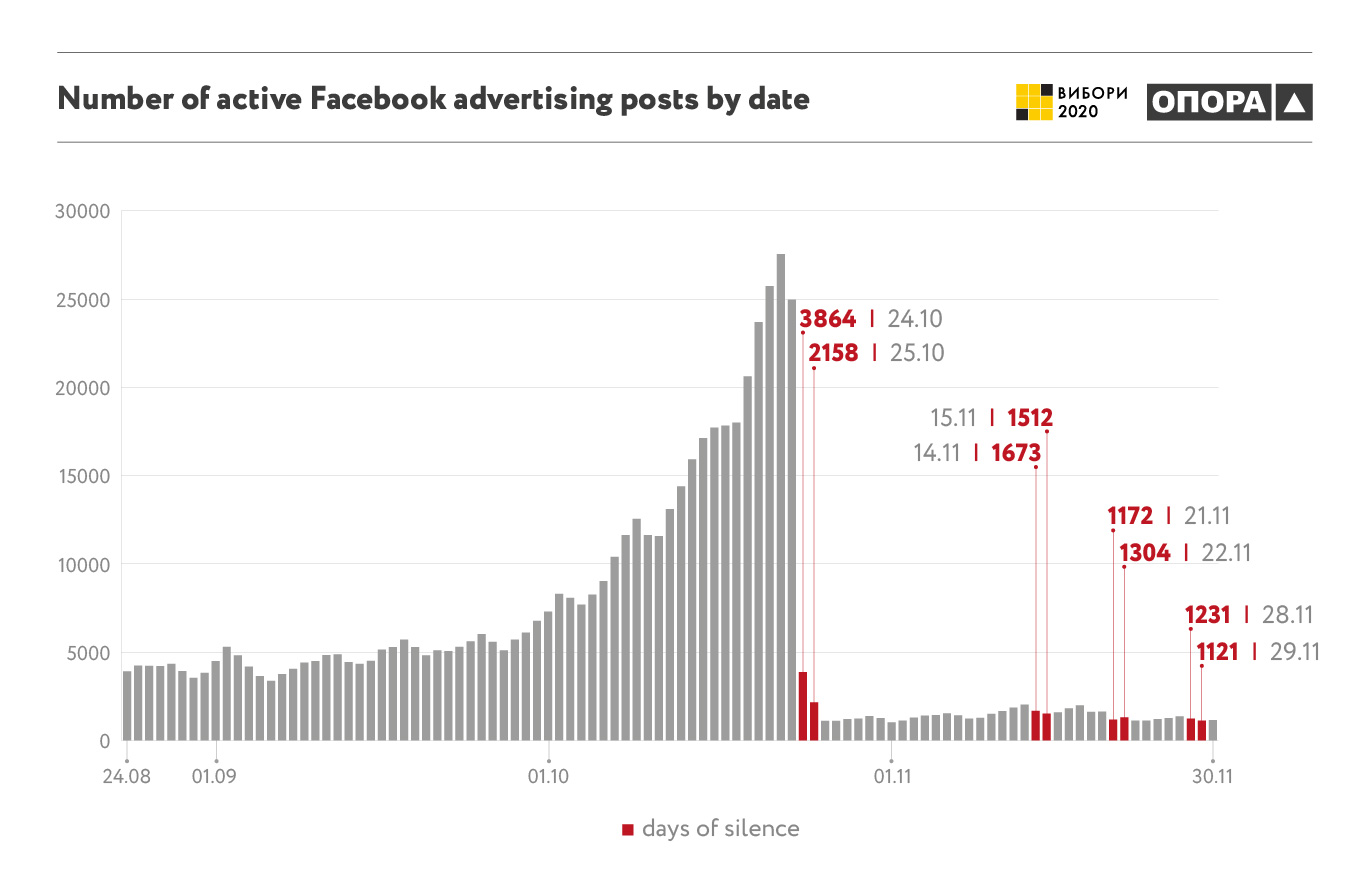

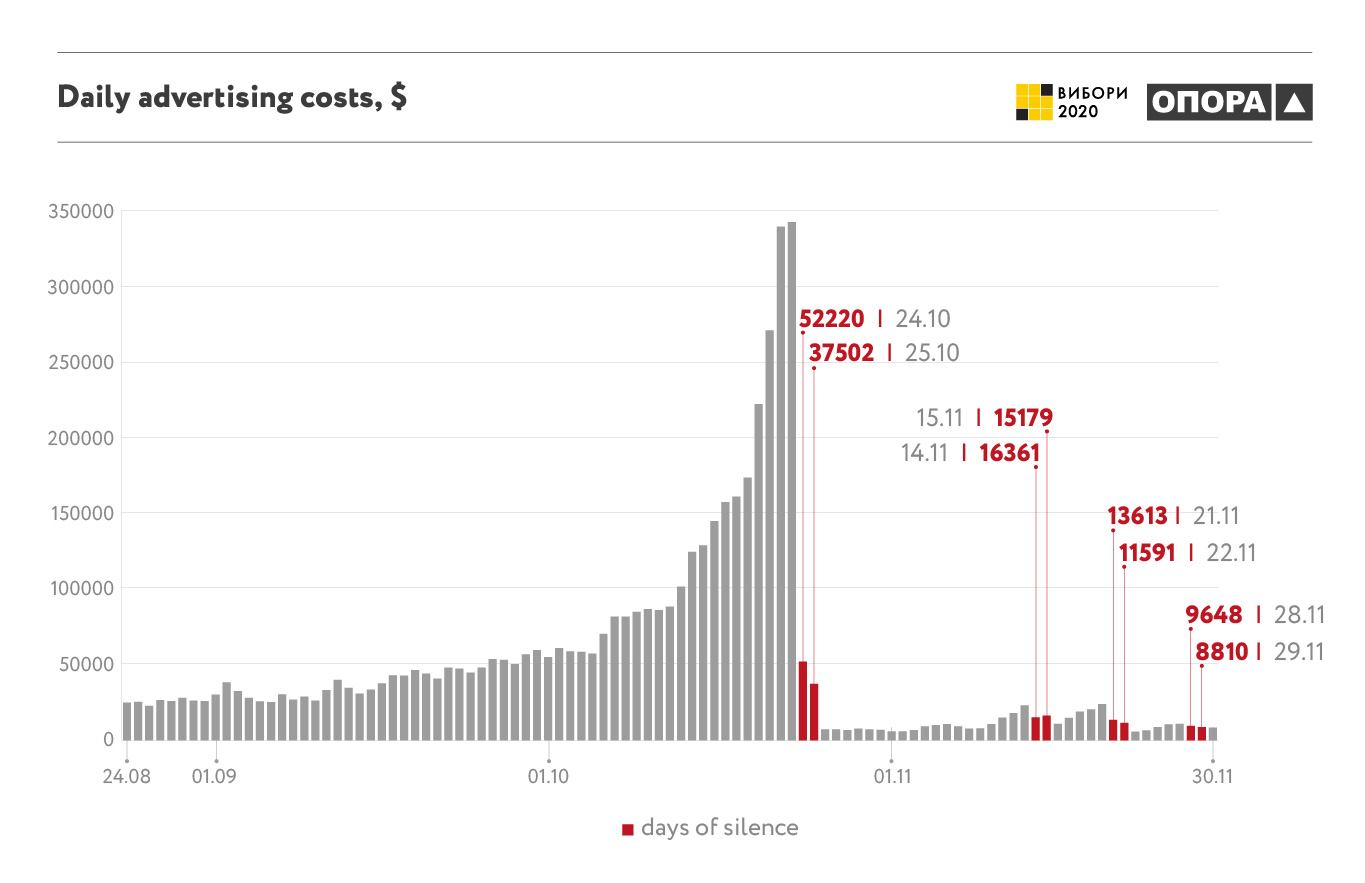

With every following election campaign, social media are becoming increasingly more important as the campaigning bandwagon for candidates and political forces. Thus, during the campaign at the regular local elections from September, 5, to October, 20, 2020, political forces and candidates for positions at different levels spent for Facebook ads ab. USD 3.1 mln (ab. UAH 84 mln). The scale of the campaign has increased, too: compared to the extraordinary elections of people’s deputies, the number of campaigning posts has almost doubled.

OPORA has multiple times highlighted the issue of the underregulated political campaigning on the Internet. In fact, the Electoral Code lacks any definition of political ads in social media as a type of campaigning. Since the election law was imperfect, candidates and parties transgressing the ban on posting ads on the “silent days” could not be sanctioned.

In this report, we tried to find out whether other countries have the “silent days” and how they are regulated under the election law, and whether the tool is worth using in the Internet age when it is hardly possible to control the abidance by the restrictions.

“Silent Days” and Elections in Ukraine

The first “silent day” came in 1989 in the the laws of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic: at the time, the ban covered only the campaigning on election day (Article 41 of the Law “On Election of People’s Deputies of Ukrainian SSR”). The same restrictions were also found in new laws of Ukraine on elections adopted in 1993 and 1997 . The present framework of the “silent days” was first included in the Law “On Election of People’s Deputies of Ukraine” adopted in 2001, and eventually captured in the Electoral Code approved in the late 2019.

According to the Electoral Code, the pre-election campaign of a candidate or a party shall finish at 24:00 on Friday preceding the election day. After that, all electoral actors shall terminate any mass campaigns on their behalf, the dissemination of campaigning materials and calls to vote for a candidate or a party in any forms (also they shall stop sharing the campaigning materials in the media and dismantle all outdoor ads). The infringement on the law entails a penalty in the amount of 5 to 10 non-taxable minimum wages (UAH 85 to 170).

In fact, the actual situation around the “silent day” in Ukraine is different from the rules set by the Electoral Code. During several recent election campaigns (the presidential and parliamentary elections in 2019 and local elections in 2020), far from all political parties and candidates followed the legal rules, even for the outdoor posters. However, the real challenge came from the campaigning on “silent days” in social media and on Internet.

The 2020 Local Elections

Most intensely the “silent day” rules were broken at local elections in October-December, 2020. According to the Facebook Ad Library, the total number of ads posted on all silent days at local elections (there were several voting rounds) was over 14,000 political ads, with the total cost was almost USD 165,000 (over UAH 4.6 mln). The number of ads shared on Facebook during the period when any political campaigning was prohibited grew 8.8 times, compared to the presidential elections; and 17.1 times, compared to the elections to Verkhovna Rada.

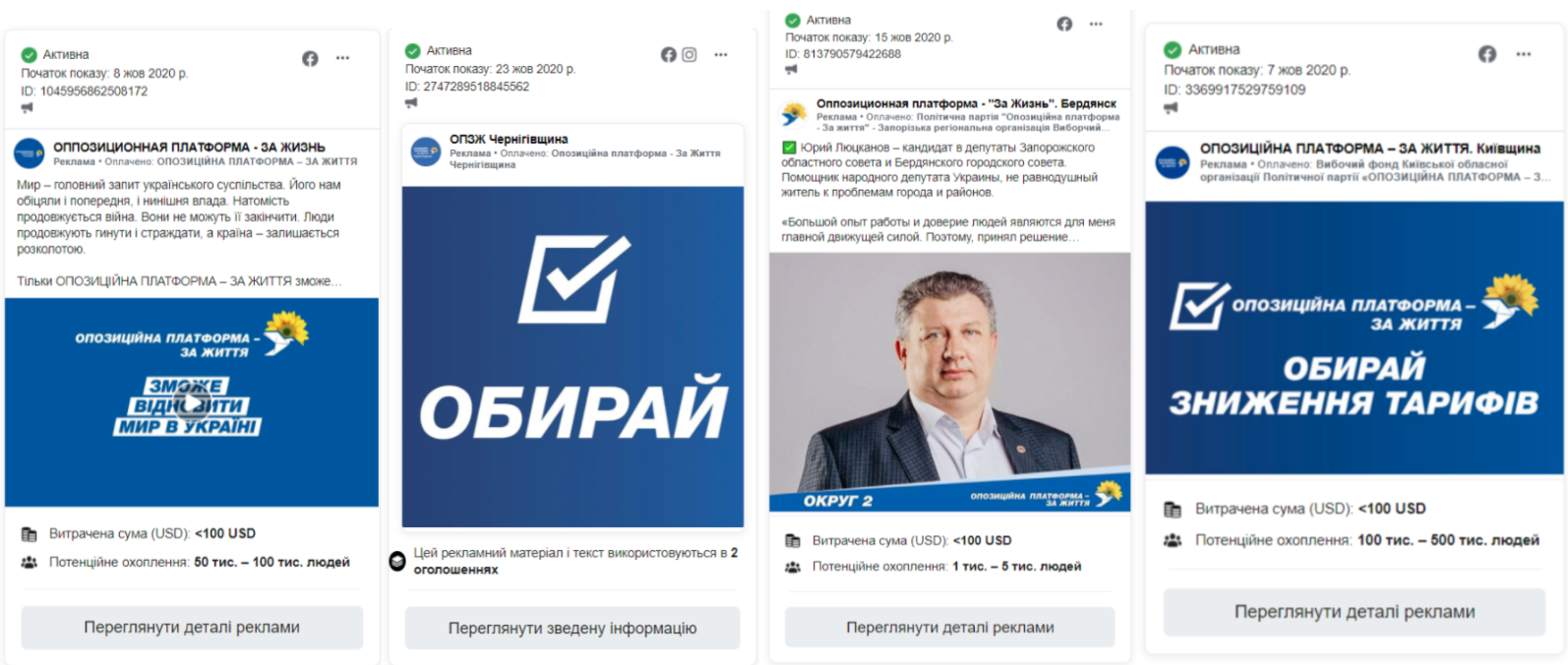

OPORA documented that certain political actors ignored the “silent day” and were actively sharing their political ads on Facebook, such as the “Opposition Platform – For Life” party. On the day before elections, and on the election day, on October, 25, the political ads were posted from the party’s central page “ОПОЗИЦИОННАЯ ПЛАТФОРМА – ЗА ЖИЗНЬ”, and from the pages of the party’s regional offices – “ОПЗЖ Чернігівщина”, “ОПОЗИЦІЙНА ПЛАТФОРМА – ЗА ЖИТТЯ. Київщина”, “Оппозиционная платформа – “За жизнь”. Бердянск”.

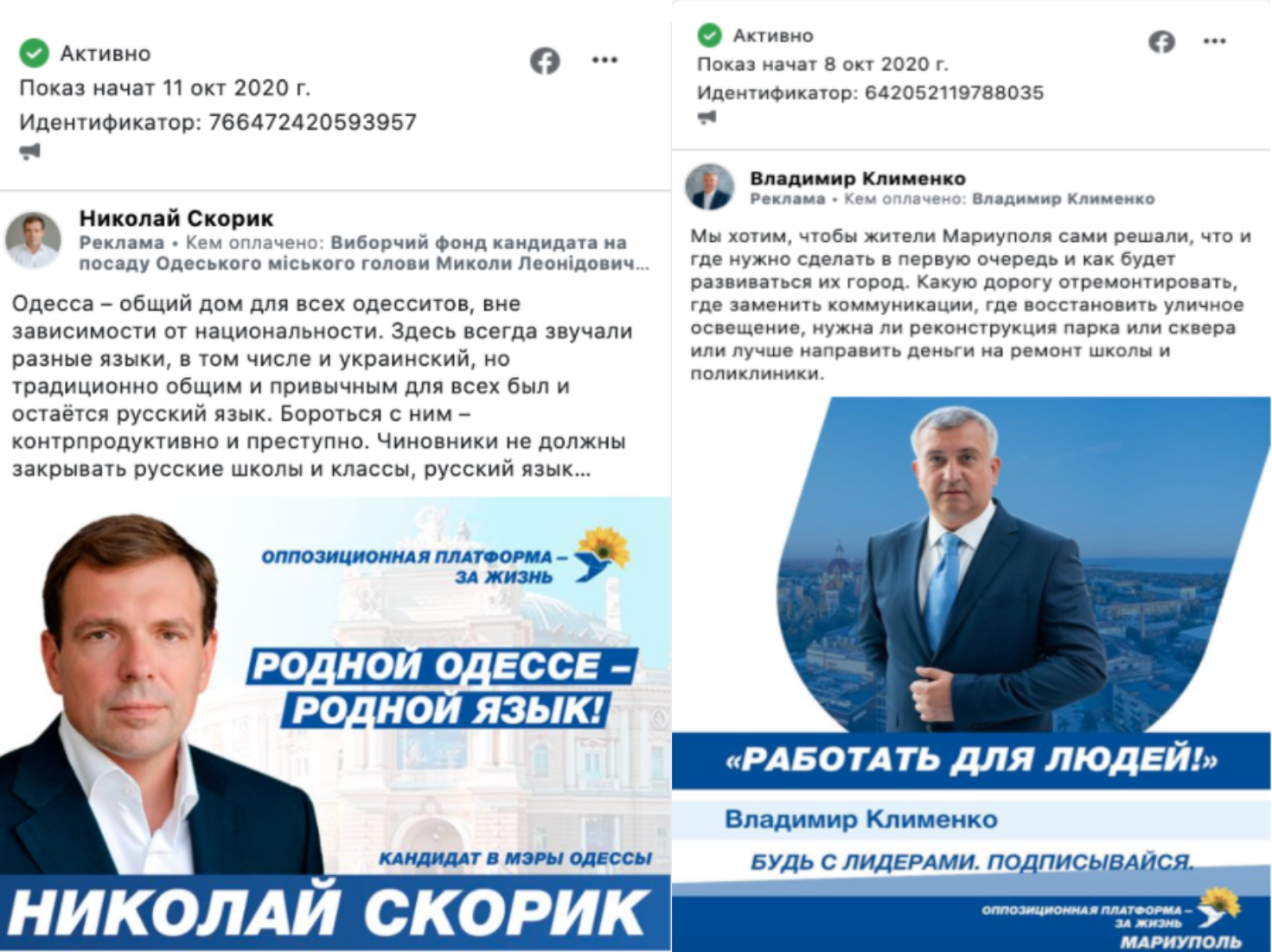

The political ads were posted on the “silent day” also by some party candidates in different cities of Ukraine – Volodymyr Klymenko who was running for the mayoral position in Mariupol; Mykola Skoryk running in Odesa; Oleksandr Popov competing for the mayoral seat in Kyiv.

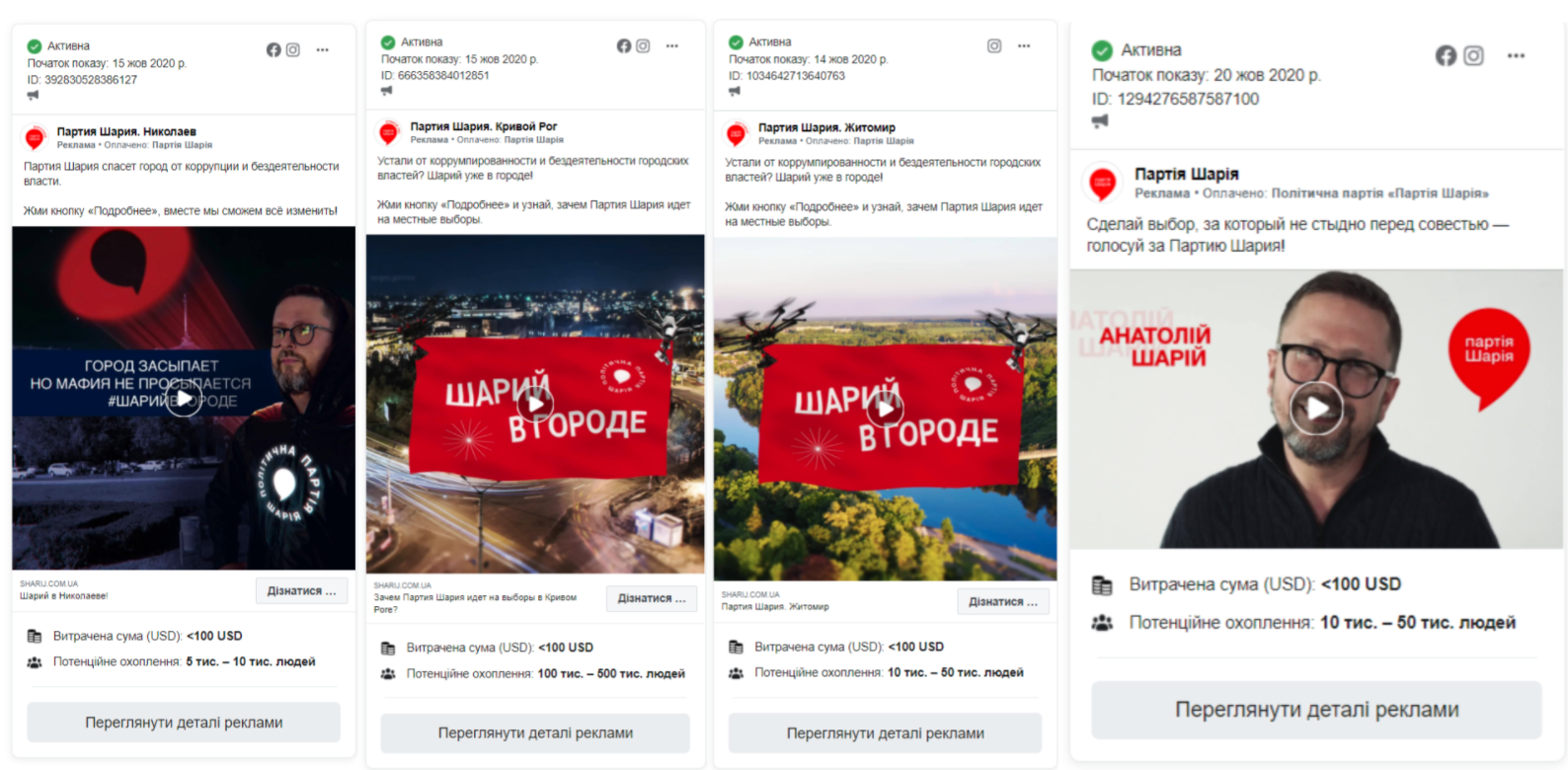

The “Shariy Party” ignored the election law in a similar fashion, and shared political ads on Facebook on the election day, and on the day before. They posted the ads from the eight party pages Партія Шарія. Вінниця, Партия Шария. Киев, Партия Шария. Запорожье, Партия Шария. Николаев, Партия Шария. Харьков, Партия Шария. Кривой Рог, Партія Шарія, Партия Шария. Житомир.

The 2019 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections

Some vivid examples of the actual impunity of political parties and candidates for various positions for breaking the silent days rules on social media can be found in the election campaigns in 2019 – the presidential elections and the extraordinary parliamentary elections.

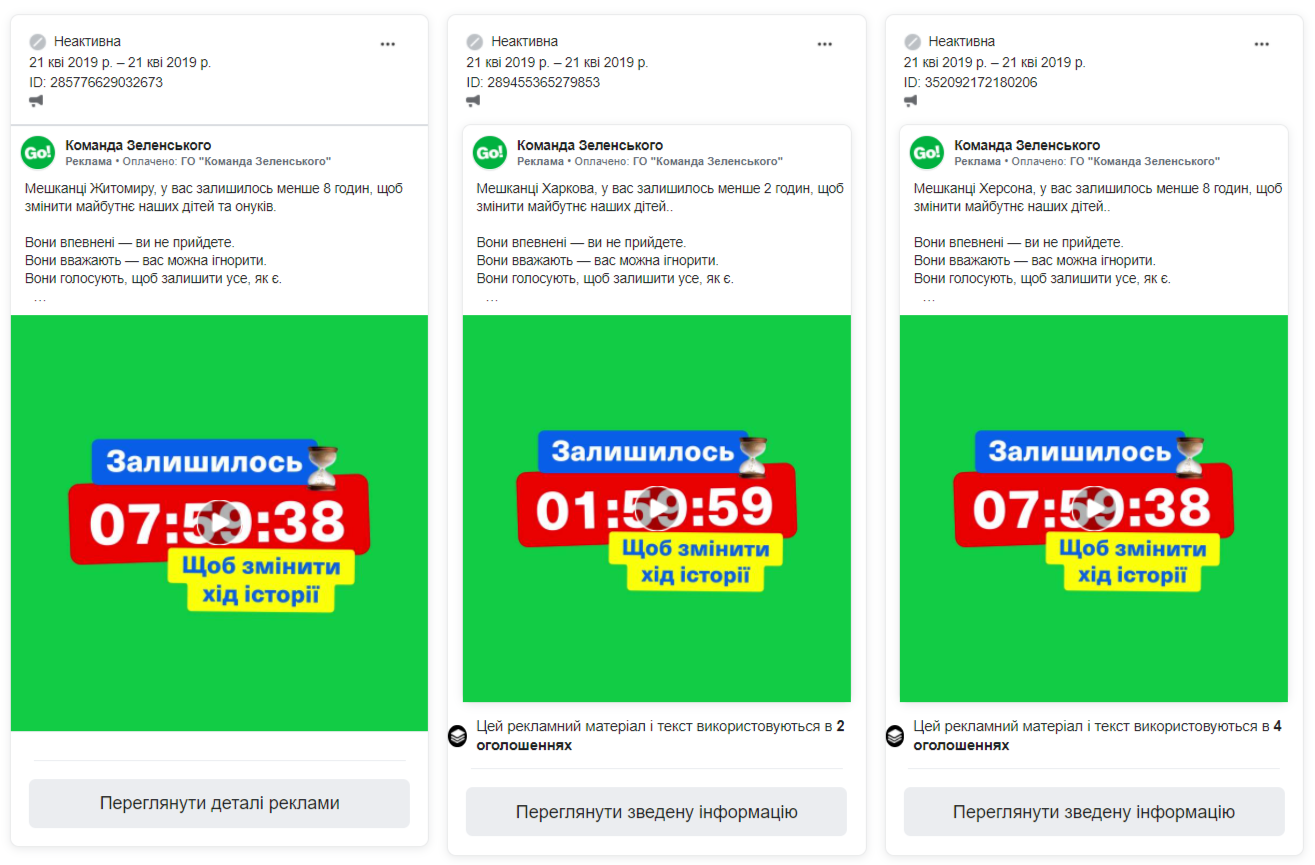

For instance, at the 2019 presidential elections, there was an intense advertising activity on the Facebook social medium coming from the presidential candidates on silent days (March, 30 and 31, and April, 20 and 21). According to the Ad Library, on these days 15% (1,595 posts) Facebook ads were posted, out of all ads shared over the election campaign for the two voting rounds. The “Команда Зеленського” page [lit. – Zelenskyi Team] is most distinct in this respect, as it was central for Volodymyr Zelenslyi’s campaign on Facebook. On April, 21, it shared 430 advertising posts and targeted them at citizens from various Ukraine’s regions.

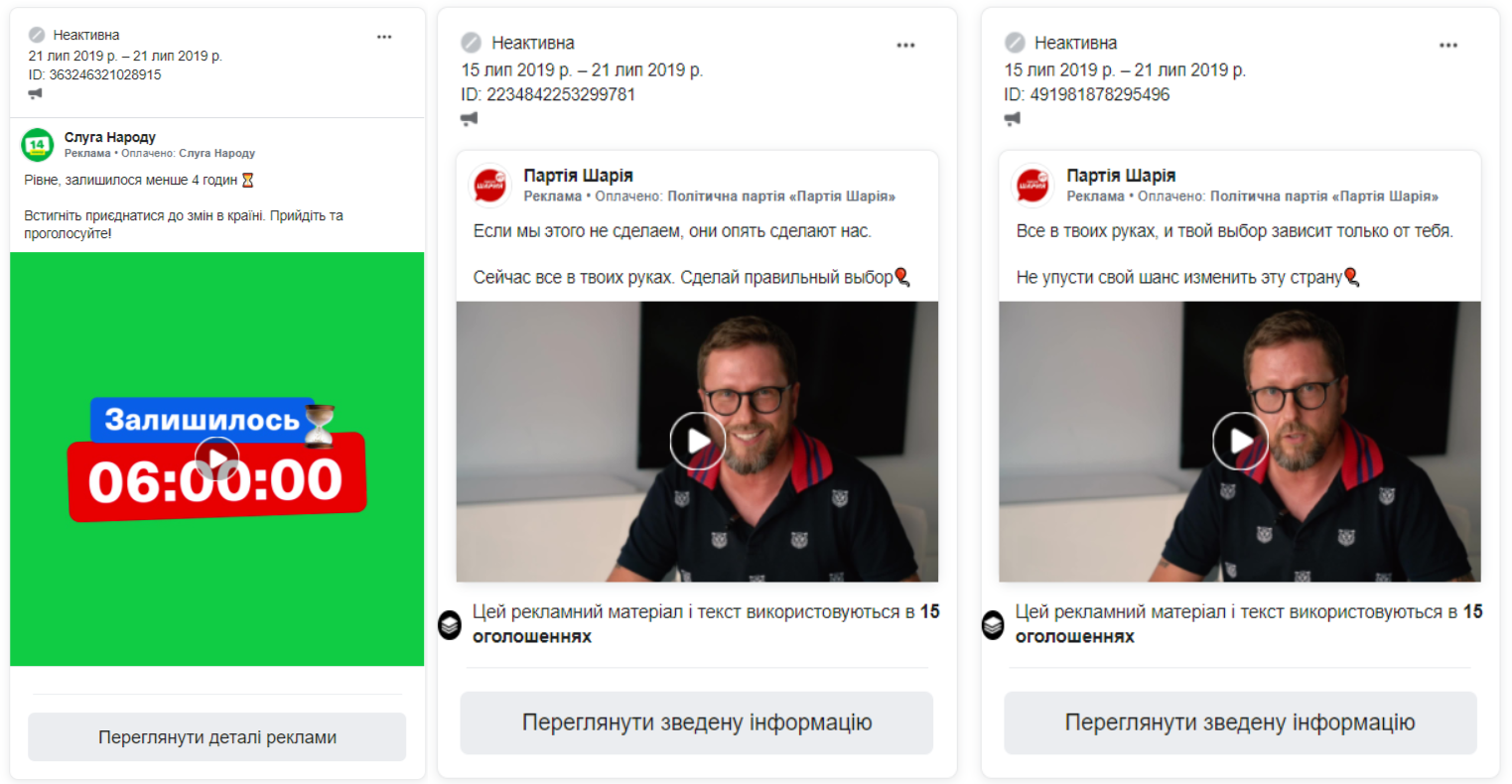

Breaking the “silent day” rules was also found during the parliamentary campaign running in July, 2019. On July, 20 and 21, 821 political ads were promoted. The “Servant of the People” party ignored the ban most intensely. ON the “silent day” they posted on their page 158 promoted ads. The “Shariy Party” joined the cause ― 8 ads.

Both presidential and parliamentary campaigns were running at the time when Facebook had the Ad Library that saves the date, time, and cost of sharing the promoted political ads. Despite the fact, no sanctions have been applied to the electoral actors. A logical question arises: do we need the “silent days” at all?

What about them?

Even though the “election silence” is a rather widespread phenomenon, we can hardly trace the first time and place when it was applied during the election process. The reasons for introducing it are simple: political campaigning before the election day and on the election day is restricted to enable voters make a well-weighted decision, with no extra pressure in the information field, and also to reduce the tension in society after the intense campaigning period. In addition to political campaigning, many countries also ban the publication of candidate rankings and informal exit polls before the polling stations are closed. It is believed that the early publication of such materials may largely affect the voting (voters would rather vote for the candidates supported by the majority).

As of today, the election silence practice is followed in 48 countries all over the world. It is rather indicative that the list of countries is dominated by new democracies, such as Eastern European countries (Ukraine, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Croatia, Russian Federation, Serbia), South America (Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina) and island countries (the Philippines, Malta, Barbados, New Zealand, etc.). The counteis that are following the rules of electoral silence in various ways also include France, Italy, UK, and Canada.

The “silent day” format is also different in different countries. The shortest of all silent period is in South Korea, Malaysia, UK, Canada, and Taiwan. There, the electoral silence is restricted only to the voting period. The longest silent days are found in Indonesia and Czech Republic. It starts three days before the election day. Most commonly, the silent period lasts from 24 to 48 hours, such as in Egypt, Mozambique, Nepal, Tunis, Ukraine, and many other countries. The scale of restrictions is different, too. For example, in Australia, it is prohibited to broadcast ads on television and radio from Wednesday midnight before the election day (that is usually on Saturday). Besides, Italy bans to mention the candidate names on television a month before the election day (except for news releases and the scheduled political ad slots). In Israel and Italy, it is prohibited to publish public opinion polls 5 and 15 days prior to elections, respectively.

There are 159 countries more in the world that have not introduced any electoral silence practice into their election laws.

Indeed, today, when the impact of social media and Internet campaigning has become evident, the efficiency of legal restrictions on political campaigning on “silent days” is questionable. The degree of restrictions in online settings is also debatable. In fact, posts and comments on social media that could fit the “campaigning” category are shared by a huge number of private users, anonymous pages and communities, while a post may go viral within a few hours. It shall also be mentioned that the online campaigning cannot be deleted as easy as the outdoor posters or ads in other media: some ads or promoted posts may be posted on social media long before the “silent days” but could be shown to users on the days when campaigning is prohibited.

Different countries are tackling the challenges differently in their legal frameworks. For example, Indonesia only restricts pre-election campaigning for candidates to elected positions and the team members they registered to be in charge of the candidate’s presentation within the information space. When registering to run for elections, candidates and their teams shall submit information on the official pages in social media which activity is monitored by the Ministry for Communications and Information. Three days before the election the accounts shall stop sharing ads or posts including any campaigning elements in the candidate’s favour. Failure to observe the rules entails the liability in the form of imprisonment up to one year and a fine of 12 mln rupia (ab. USD 850).

The Polish law stipulates that any form of political campaigning shall be prohibited on the day before the elections and on the election day. The ban covers all media, also online, however, such that are located on the Poland’s territory directly. Moreover, Polish law does not require dismantling any outdoor posters or deleting online ads that had been installed or posted before the “silent day”.

“Silent days” drew special attention befote the recent presidential elections in France. According to the French law, on the day before the elections, and on the election day, any materials are prohibited if they campaign in favour a candidate or discredit any candidate. In case the rule is broken, a fine shall be paid up to EUR 75,000. In 2017, several hours before the legal restrictions entered into effect, the archives of correspondence were posted online from the private email of the then French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron. Since the documents were posted shortly before the “silent day”, neither the mass media nor Macron’s team were able to comment on them. However, the publication, commonly labelled on the Internet as #MacronLeaks, went viral on social media. As a result, voters could receive the information on this data only from posts on such social media as Twitter, Facebook, and the WikiLeaks resource. The French case well illustrates how the legal restrictions led to the tampering intending to discredit a candidate.

Therefore, in reality, the “silent days” are not as widespread practice as it might seem. On the other hand, many consolidated democracies rejected the regulation of campaigning on the election day. Further application of this practice in Ukraine also raises many questions, especially in a situation of the actual impunity of electoral actors for circumventing the rules through social media, and for using the covert campaigning. At the same time, in the countries where “silent days” are followed, the sanctions for the violation are more tangible than presently in Ukraine.

Thus, the Ukrainian legislators need to make up their minds whether to expand the meaning of political campaigning to cover social media and develop the mechanisms of bringing electoral actors to justice for breaking the rules, or to cancel the “campaign silence” days for all electoral actors to ensure equal opportunities in sharing their ads on election days.

The “silent day” format is also different in different countries. The shortest of all silent period is in South Korea, Malaysia, UK, Canada, and Taiwan. There, the electoral silence is restricted only to the voting period. The longest silent days are found in Indonesia and Czech Republic. It starts three days before the election day. Most commonly, the silent period lasts from 24 to 48 hours, such as in Egypt, Mozambique, Nepal, Tunis, Ukraine, and many other countries. The scale of restrictions is different, too. For example, in Australia, it is prohibited to broadcast ads on television and radio from Wednesday midnight before the election day (that is usually on Saturday). Besides, Italy bans to mention the candidate names on television a month before the election day (except for news releases and the scheduled political ad slots). In Israel and Italy, it is prohibited to publish public opinion polls 5 and 15 days prior to elections, respectively.

There are 159 countries more in the world that have not introduced any electoral silence practice into their election laws.

Indeed, today, when the impact of social media and Internet campaigning has become evident, the efficiency of legal restrictions on political campaigning on “silent days” is questionable. The degree of restrictions in online settings is also debatable. In fact, posts and comments on social media that could fit the “campaigning” category are shared by a huge number of private users, anonymous pages and communities, while a post may go viral within a few hours. It shall also be mentioned that the online campaigning cannot be deleted as easy as the outdoor posters or ads in other media: some ads or promoted posts may be posted on social media long before the “silent days” but could be shown to users on the days when campaigning is prohibited.

Different countries are tackling the challenges differently in their legal frameworks. For example, Indonesia only restricts pre-election campaigning for candidates to elected positions and the team members they registered to be in charge of the candidate’s presentation within the information space. When registering to run for elections, candidates and their teams shall submit information on the official pages in social media which activity is monitored by the Ministry for Communications and Information. Three days before the election the accounts shall stop sharing ads or posts including any campaigning elements in the candidate’s favour. Failure to observe the rules entails the liability in the form of imprisonment up to one year and a fine of 12 mln rupia (ab. USD 850).

The Polish law stipulates that any form of political campaigning shall be prohibited on the day before the elections and on the election day. The ban covers all media, also online, however, such that are located on the Poland’s territory directly. Moreover, Polish law does not require dismantling any outdoor posters or deleting online ads that had been installed or posted before the “silent day”.

“Silent days” drew special attention befote the recent presidential elections in France. According to the French law, on the day before the elections, and on the election day, any materials are prohibited if they campaign in favour a candidate or discredit any candidate. In case the rule is broken, a fine shall be paid up to EUR 75,000. In 2017, several hours before the legal restrictions entered into effect, the archives of correspondence were posted online from the private email of the then French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron. Since the documents were posted shortly before the “silent day”, neither the mass media nor Macron’s team were able to comment on them. However, the publication, commonly labelled on the Internet as #MacronLeaks, went viral on social media. As a result, voters could receive the information on this data only from posts on such social media as Twitter, Facebook, and the WikiLeaks resource. The French case well illustrates how the legal restrictions led to the tampering intending to discredit a candidate.

Therefore, in reality, the “silent days” are not as widespread practice as it might seem. On the other hand, many consolidated democracies rejected the regulation of campaigning on the election day. Further application of this practice in Ukraine also raises many questions, especially in a situation of the actual impunity of electoral actors for circumventing the rules through social media, and for using the covert campaigning. At the same time, in the countries where “silent days” are followed, the sanctions for the violation are more tangible than presently in Ukraine.

Thus, the Ukrainian legislators need to make up their minds whether to expand the meaning of political campaigning to cover social media and develop the mechanisms of bringing electoral actors to justice for breaking the rules, or to cancel the “campaign silence” days for all electoral actors to ensure equal opportunities in sharing their ads on election days.

Olha Snopok, Anastasia Romaniuk, experts in social media monitoring